The Washington Post: Parade Magazine - August 1992 Edition: Can We Put The War Behind Us?

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Little by little , the United States is normalizing

its relationship with an old enemy, but.. Not All The Wounds Have Healed

by James Webb

We are preparing to leave Tan San Nhut Airport in Saigon (officially called Ho Chi Minh City by the Communists) after three weeks inside Vietnam. As I carry my bags toward the X-ray machine, a uniformed officer at a nearby wooden table summons me. He has been waiting. He knows my face. He asks to see my passport and exit papers. When I begin to answer in Vietnamese, he cuts me off. “Yes,” he says. “We know you speak Vietnamese.”

I bring my bags to another table. He begins to point and probe, telling me he is acting on orders “from above.” Every fold in every bag is delved into, every zippered compartment checked. Even my shaving kit is taken apart. My personal papers—including notes and the addresses of friends—are taken from my briefcase into another room to be photographed. Eleven rolls of undeveloped film are confiscated. Our Labor Ministry host, who has been with us the entire trip, now watches helplessly, offering frequent apologies for the conduct of his Interior Ministry colleagues.

As I stand with my belongings strewn across the table, a television crew

a U.S. news show is escorted through Customs without opening a bag. I had watched them the evening before as they filmed on the roof top of the exclusive Rex Hotel, far removed from the country and its people, surrounded only by foreign guests who had come in search of business deals and waiters who had been carefully screened by the government for attitude and family background.

I am becoming angry at the arrogance of my inspectors. I slammed a suitcase onto the table, drawing threatening stares. And then I learn a valuable lesson from my friend Ca Van Tran, who has endured such indignities before.

Ca is screaming at them too. They are warning him that he is on the edge of arrest. They confiscate four videotapes that already had been screened for political content. Last summer in Ho Chi Minh City, they pulled him from his hotel and detained him for four days of questioning, never giving him a reason. They have kept his son for 17 years. They have all but destroyed his family.

Furthermore, Ca is a Viet Kieu, one of the nearly 2 million “overseas Vietnamese” who have fled the Communist system. Their success in free societies, and their visible wealth when they return to Vietnam, is a reminder both of the strength of the Vietnamese culture and the failure of the Communist system. While some Hanoi moderates seek to cultivate the Viet Kieu as a future source of funds and expertise, the hardliners fear them even more than they do the Americans.

But for Ca, this is bigger than himself, bigger than his family, bigger even than the government that is debating whether he should be cultivated or feared. He backs off and whispers to me, “They want us to get so mad, we'll never come back. Then who's going to help the people? Who's going to give them hope?”

A mistake, both during the Vietnam war and after, has been our failure to listen to people like Ca Van Tran. Even today, government officials who pride themselves on having consulted with “Asia experts” when considering policy toward Vietnam rarely include those who were once its citizens and who have lived its tragedies.

Ca was literally born to war, his first screams echoing inside the tiny earthen bunker where his family had retreated as his village in Quang Nam was bombed by French aircraft in 1951. His oldest brother was killed a year later fighting the French, before the Viet Minh became the exclusively Communist Viet Cong. After the country was divided in 1954, Ca’s family served the South Vietnamese government, but the family shrine was sometimes desecrated because his Viet Minh brother's picture hung underneath it. Ca’s school was blown up by the VC during the 1968 Tet offensive. Having a gift for language, Ca then spent three years with the U.S. Marines as an interpreter and later moved to Saigon, where he worked for the United States Agency for International Development.

On the day Saigon fell in 1975, Ca escaped with his wife on one of the last boats to make it to international waters.

Arriving in the United States with nothing, he found work as a janitor in Virginia’s suburban Springfield Mall, then as the manager of a Mexican restaurant and later as a courier for Federal Express. After a few years, he took the plunge into entrepreneurship. Today he lives in a million-dollar home, dabbles in real estate and owns four restaurants—

his own chain called Taco Amigo.

But he could never forget what he left behind.

In the final hours before Saigon’s fall, Ca and his wife had searched frantically—and unsuccessfully—for their year-old son, who was being baby-sat by Ca’s sister. Today, 17 years later, Communist authorities still refuse to allow them to join his parents. When Da Nang fell, one of Ca’s brothers was brutalized for having served the Americans. He and two of his children then died trying to escape Vietnam by boat in 1979. A sister lost two husbands killed in battle fighting for the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), only to perish along with her third husband and six other family members while trying to flee the country. Another brother who fought for the ARVN was sent to a “reeducation camp” for two years, then forcibly resettled into a “new economic zone,” where he now lives in a ramshackle community along with other former ARVN families. Husband of another sister spent seven years in a reeducation camp, then also was relocated to a new economic zone.

“For 15 years, all I did was work,” Ca says. “If I stopped working, I would

Start remembering. It was a nightmare. There was nothing I could do to help.”

Like many of the nearly one million Vietnamese Americans, Ca’s only re

course for years was to send his family money. (Financial support by the Viet Kieu to family members has been a principal source of outside revenue for Vietnam, amounting to an estimated $500 million a year.) Then, in late 1990, his father became ill, and Ca brought his 3-year old daughter back to Vietnam for what he thought would be a final visit.

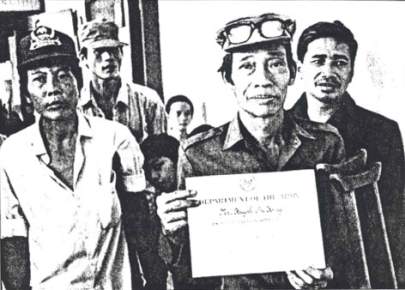

The extent of the suffering overwhelmed him. “I realized it wasn't just my family, it was the whole country. I saw veterans without legs pushing themselves through the marketplace on pieces of cardboard. The villagers in central Vietnam, my home, were starving. The whole country was a jail. Nobody smiled. I just had to do something.”

Upon his return, Ca founded Viet Nam Assistance for the Handicapped. Its mission is to help those who were disabled during the war—with “equal access” for soldiers from both sides as well as for civilians, but with special attention to ARVN veterans who have received nothing Since the communists took power. In a key gesture this year the million member Disabled American Veterans signed an assistance agreement with Ca's organization, marking the first time Vietnamese Americans and American veterans are working together inside Vietnam.

But Ca has walked a delicate tight rope. Many in the Hanoi government fear he is working for resistance groups in the U.S., causing him continuous problems inside Vietnam. At the same time, many Vietnamese in the U.S. whisper that he is too close to the Communists, creating problems at home. He remains philosophical.

“People who criticize what I'm doing are living at the bottom of the well,” says Ca. “They don’t know how big the sky is. I've told the Communists the system has to change. We have to show them how. No matter what we do they’ll still make business deals with other countries, and next year the U.S. will lift the trade embargo. Where's that money going to go? A lot of the Viet Kieu who criticize my program send money to their families, and some secretly invest inside the country. But who's going to help the people in the villages and the ones who were destroyed by the war?”

For all the criticism he has received, and for all the frustrations he has endured, Ca is helping to shape the future of his native country. Vietnam's combative Communists—who, during their brief existence, have fought the French, the Americans, the Chinese, the Cambodians and non-Communist Vietnamese of all persuasions, others—are now debating the future direction of the country. With the collapse of their Soviet patron and the resulting disappearance of some $2 billion worth of aid a year. Hanoi has begun opening up to private investment.

At the same time, the political system remains tightly controlled. A moderate element, many of its members schooled in Eastern Europe, has worked hard to open new contacts in the U.S.—including with people such as myself, who will never apologize for having fought against communism. Others, particularly those who embrace the repressive role model of post-Tiananmen China, are deeply threatened by our presence. As one Foreign Ministry official said to me, only half in jest, “Some of our people still sleep with guns underneath their pillow, waiting for the Americans to reinvade.”

"I realized," Ca said, "it wasn't just my family. The villagers in central Vietnam were starving. The whole countrywas a jail. Nobody smiled. I just had to do something."

Traveling to Vietnam with Ca and Michael McGarvey, a friend from my Marine Corps unit during the war, I saw first-hand how intense this debate has become and how unresolved it still is. I journeyed the entire length of the country by car, from Hanoi through the Mekong Delta, not as a journalist or a political figure but as an American on a private humanitarian mission. I conversed with hundreds of Vietnamese in their own language—not through a government interpreter—including many who had never before met an American. I spoke with the winners and the losers from the war that ravaged the country and at the same time scarred America’s sense of self. I bantered with the people of Hanoi in their tiny shops or as they lazed on the banks of the city’s many lakes in the midday sun. They were curious, friendly and clearly underworked—a marked contrast to the bustle of Ho Chi Minh City. As we drove through the northern provinces, swarms of villagers came out to stare at us whenever we stopped along the primitive roadside, some marveled at Mac's girth as they poked their own tight bellies and us for food. Others pulled gently at the red hair on my arms, never having touched a Caucasian before.

I met the stares of former enemy soldiers in the provinces of central Vietnam and talked with villagers in the valley where I had fought as a Marine. For all that has been written of bombs over Hanoi and tanks rolling into Saigon, this area, which straddles both sides of the old demilitarized zone, was the most devastated by the war. And it is still recovering from one of history's most vicious and enduring crossfires.

I drove past numerous old landmarks, bare stretches plowed under like Carthage. where vast American bases once stood, The rubbled earth of places such as Gio Linh, Con Thien, Phu Bai, An Hoa, Liberty Bridge, Long Binh and Chu Lai remains hauntingly empty, marked by millions of small trees planted by reeducation-camp prisoners.

I saw much of the country for the first time, journeying through Hue, Da Nang, Nha Trang, Ho Chi Minh City and Can Tho, all the way to the crowded temples of Chau Doc on the Cambodian border. I met with government officials who were anxious to move forward. I sat restlessly with leaders of Communist veterans

in the North and South, who ended both meetings by plugging tour packages to old battlefields complete with “real Communist heroes” as guides. I visited hospitals and clinics desperate for modem equipment and financial assistance. I remembered the past and argued about its impact on the future.

But as we moved into the still-contentious South, we also were watched, wiretapped, spied upon and suborned. At home I have written extensively regarding the difficulties former ARVN

soldiers still face inside Communist Vietnam and have argued that the U.S. should seek protections for these for veterans as part of the of normalizing diplomatic relations between our two countries. I raised this issue in every meeting with government and military officials at every stop of the trip. My visa had been denied for more a year because of these views.

Someone in the Interior Ministry—a combination of the FBI and secret police—decided to bring the hammer down. And so, at the end of our visit, Ca and I found ourselves standing before the belligerent Customs officials whose mission was to strip us down, humiliate us, see if we were spies.

The Mandarins who whisper of Ca’s “dealings with Hanoi" from the safety of their homes in the U.S. do not comprehend the risks he takes. Nor can they appreciate the progress he has begun to make. When we visited the clinic his group is ———_ for assisting, in the Mekong Delita capital of Can Tho, more than 100 former ARVNs were waiting for us. Word had gotten out without official publicity that Ca was back in town. Most were severely wounded, including several double amputees and at least one triple amputee. None of them had ever visited the clinic, whose director is a former VC officer and whose physician is from Hanoi. We had little to offer, other than the promise to ask for financial help for them (former ARVNs must pay for their own treatment) and

the hope that comes from knowing they have not been forgotten. But, after our return, there were several letters thanking us for those small glimmers.

In our last night in Ho Chi Minh City, Ca brought four family members, including his 87-year-old father, into the exclusive Rex Hotel. As we dined in the fifth-floor restaurant, I noted that his family were the only “normal” Vietnamese I had ever observed in the hotel. The Rex, cheap by U.S. standards, would cost a Vietnamese four months’ wages just to cover a night's room charge—if the government granted him permission to stay at the hotel.

Ca's father was particularly entranced, The old man sat at the polished table in the traditional farmer's light-blue pajamas, at times so stunned by the beauty and opulence of the hotel that he forgot to eat. After dinner we walked onto the terrace. An Indian lawyer sat nearby, talking of his branch offices in Phnom Penh and Hanoi. Further off, several Australians were drinking beer and making lewd comments at an unsmiling waitress. Closer to us, three French couples were talking animatedly.

The old man stopped for a moment to peer at a brightly colored bird that was whistling inside a cage. Then he shuffled slowly to the edge of the terrace, pausing to touch a shrub that had been sculptured into the likeness of a deer. Now he — carefully over the edge, looking at the street. Streams of people on motorbikes were orbiting a small traffic circle. Hundreds of others frolicked in a brightly lit park.

Watching the awed old man stare down at the mundanity of city traffic, I felt my heart melt. He had lost a son to the French, two sons-in-law to the Communists, 11 family members dead trying to escape the war's cruel aftermath, others devastated and repressed, still others scattered across the sea. I remarked to Ca about how ironic it was that a man who had seen so much tragedy in his lifetime would be so fascinated by a hotel restaurant and the swirl of traffic.

“Well,” said the old man's youngest son, his eyes moist, “he’s never been this high before.”

For more information, write;

Viet-Nam Assistance for the Handicapped,

Dept. P, P.O. Box 6554, McLean, VA, 22106.